Timpanogos Chief Black Hawk born c1835 died 1870

The life of Timpanogos Chief Black Hawk had come full circle when, on September 26, 1870, at the age of 35, the Chief's loving kin honorably laid him to rest on a hillside overlooking Spring Lake above Payson, Utah, the place of his birth. Black Hawk had crossed over to the spirit world and into the arms of his ancestors.

Just 49 years following Black Hawk's burial, on September 20, 1919, members of the Mormon church robbed Black Hawk's grave and put his remains on display in the window of a hardware store for amusement, which will be discussed in greater detail further on.

Black Hawk was born into a royal lineage of Timpanogos leaders. The Timpanogos Tribe, a band of the Snake Shoshone, documents his ancestry back to 1776, when Spanish explorers Dominguez and Escalante met his great-grandfather, Chief Turunianchi the Great of the Timpanogos Nation. Chief Turunianchi had a son named Moonch, who was the father of Chief Sanpitch (Tenaciono). Sanpitch's mother, Tanar-oh-which, gave birth to several children. Chief Sanpitch was the father of Black Hawk, and the eldest of seven siblings, all of whom became Timpanogos leaders: Wakara, Sowiette, Arapeen, Ammon, Tabby, Tintic, Kanosh, and Grospean. See Timpanogos Biography; The Utah Black Hawk War

The tribe knew him Black Hawk as Nu'intz. By the age of thirteen, Black Hawk's peaceful life along the Wasatch Mountains was disrupted when Mormon settlers arrived in 1847. In 1849, Brigham Young, the president of the LDS Church, ordered the Mormon militia to exterminate the Timpanogos Nation. See Battle Creek Canyon Massacre

When the boy Nu'intz was at Battle Creek Canyon, Pleasant Grove, Utah, he experienced trauma after witnessing the senseless and brutal murders of three of his relatives by the Mormon Militia. Captain Scott ordered his troops to take Nu'intz and 14 of his family members captive. A year later, they were taken to Fort Utah, where he witnessed the decapitation of 70 of his people. Brigham Young, in a supercilious manner, labeled Nu'intz "Black Hawk," named after the famous Sauk chief of the Black Hawk War in Illinois in 1832. In 1866, Nu'intz was mortally wounded at Gravely Ford while trying to save the life of his friend and fellow warrior, White Horse.

On July 1, 1915, William Probert wrote a letter to my great-grandfather Peter Gottfredson the following:

Mr. Peter Gottfredson, Springville, Utah

There are probably a dozen men in Utah who claim the honor of killing Black Hawk, none of which is true.

It is true that Black Hawk was severely wounded in the fight at Gravelly Ford on the Sevier River, near what is now called Vermillion; but he lived three of four years after receiving the wound; and before his death Black Hawk obtained permission from the military authorities of the Territory to visit all the places where he and his tribe had caused trouble or raided. And accompanied by a few (seven or eight) warriors, Black Hawk visited every town and village from Cedar City on the south to Payson on the north and made peace with the people. On his mission of peace he was provided with an escort, usually from two to six citizens, from town to town. Ansel P. Harmon and myself acted as such escort from Holden to Scipio, Millard County.

(Signed) William Probert.

Manti, Utah, Feb. 12, 1915.

Box 109.

In 1865, during the height of the Black Hawk War, Black Hawk served as the War Chief of his tribe for 14 months while his uncle Tabby held the position of the nation's principal chief. The following year, Black Hawk received devastating news that his father, Sanpitch, had been murdered at Birch Creek, near the Mormon settlement of Moroni, Utah. In response to this tragedy, Black Hawk persuaded Tabby to end the bloodshed. From 1867 until his death in 1870, they worked together to advocate for peace. See Timpanogos Chief Sanpitch Murdered

Mormon leaders were able to colonize the lands of the Timpanogos without any treaty, title, deed, or compensation; essentially, they stole it. In 1867, Brigham Young and his 55 wives celebrated the completion of the Salt Lake Tabernacle, which was built on a Timpanogos burial ground. Meanwhile, the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, and the Salt Lake Temple, regarded as the "Holy of Holies," was in its 17th year of construction in 1870.

In stark contrast, Chief Black Hawk, a man who bore the weight of injustice, whose only crime was being Indigenous to Utah Territory, was slowly making his last journey home, suffering from complications of the gunshot wound that never properly healed. Taking him 12 or more days by horseback to ride 180 miles from Cedar City to Spring Lake. Black Hawk was in severe pain, gaunt and hollow-eyed, and knew he would soon die.

Utah Chief Black Hawk's Grave Robbed For Amusement

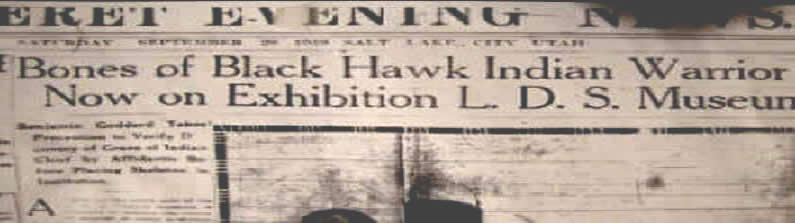

Just 49 years following Black Hawk's burial, on September 20, 1919, members of the Mormon church robbed Black Hawk's grave. The following article appeared on the front page of the Deseret News with the headline, "Bones of Black Hawk Now on Exhibition L.D.S. Museum." The reporter writes that the remains of Black Hawk had been on public display for amusement in the window of a hardware store in downtown Spanish Fork, Utah. When Benjamin Guadard, the man in charge of the L.D.S. Museum, acquired the remains for public display on the recently completed Temple Square in downtown Salt Lake City to attract visitors.

Just 49 years following Black Hawk's burial, on September 20, 1919, members of the Mormon church robbed Black Hawk's grave. The following article appeared on the front page of the Deseret News with the headline, "Bones of Black Hawk Now on Exhibition L.D.S. Museum." The reporter writes that the remains of Black Hawk had been on public display for amusement in the window of a hardware store in downtown Spanish Fork, Utah. When Benjamin Guadard, the man in charge of the L.D.S. Museum, acquired the remains for public display on the recently completed Temple Square in downtown Salt Lake City to attract visitors.

In Phillip B Gottfredson's book, Black Hawk's Mission of Peace, Phillip has published several affidavits that are in the news article. One example is Ben Bullock's account:

Quote: In 1911, I became interested in what is known as the “Syndicate mine,” located on Santiquin mountain, a little southeast of Spring Lake Villa. Several of the old settlers of Spring Lake Villa knew the old “Black Hawk” has been on the mountain near where we was working this property. At my leisure moments I would hunt for the spot where “Black Hawk” was buried and one day one of the miners, William E. Croft reported what he supposed to be “Black Hawk’s” grave. This started an investigation and Mr. Croft along with Lars L. Olsen and myself uncovered the remains of “Black Hawk,” which were buried in a large quartzite slide. Three feet of rock were taken from the skeleton, and upon uncovering it, we found the remains in a sitting posture. The first article we saw was a china pipe, which, was laying upon the top of his head. Then we discovered the saddle, the remains of the skeleton, portion’s of his horses bridle that had been buried with him; sleigh bells, ax, bucket, beads, part of an old soldier coat with the brass buttons still intact. All of these were removed very carefully, and for safety deposited them with the Spanish Fork Co-op where they were exhibited for several days.

Subsequently at the suggestion of Commander J. M. Westwood I secured these remains and conveyed them to the L.D.S. Church Museum on temple block, suggesting that they should be placed on exhibition there and preserved. – Ben H. Bullock.

Phillip also wrote, "My father, Merrill E. Gottfredson, remembered seeing his remains when they were on display in the hardware store window when he was just a boy of 12. For decades, remains of Black Hawk, and those of an Indian woman and a child, were also on display in the church museum for the public to see as mere curiosity. My father took me there at the age of twelve, and I will never forget seeing Black Hawk's remains on display in a glass case."

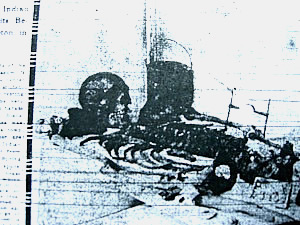

"They say there are no known photos of Black Hawk, there's one and it appeared on the front page of the Deseret News Paper. Just 49 years had passed since Black Hawk had been laid to rest, when members of the LDS Church looted his grave.  Accompanying the article is a photo of William E. Croff standing in the open grave, grinning ear to ear, while holding in his hands the skull of Black Hawk," said Phillip Gottfredson.

Accompanying the article is a photo of William E. Croff standing in the open grave, grinning ear to ear, while holding in his hands the skull of Black Hawk," said Phillip Gottfredson.

Gottfredson describes in his book how the living descendants of Black Hawk were outraged, but their angry voices fell on deaf ears. Mormon Church leaders made no apologies and expressed no conscience or remorse. Despite a federal law passed in 1906 called the Graves Protection Act, descendents of Black Hawk had no real legal recourse until the enactment of the National American Graves Protection Reparation Act, or NAGPRA, passed in 1994.

It took an act of Congress, the help of National Forest Service archeologist Charmain Thompson, and the humanitarian efforts of a boy scout Shane Armstrong to find and rebury the remains of Chief Black Hawk at Spring Lake in May of 1996. In a private conversation with Shane, and his mother, Shane explained to Phillip, "I felt it in my heart I should find Black Hawk's remains," he said. Inspired at the age of 14, Shane, on his own, makes contact with Thompson. He explained the frustration of finding Chief Black Hawk's remains, "no one knew where they were," said Shane Armstrong. Gottfredson details n his book how after a month of searching they located the lost remains of the Chief in a basement storage room in a cardboard box on the campus of Brigham Young University.

On November 24, 2008, the Utah State Division of Indian Affairs awarded Shane Armstrong the prestigious Indigenous Day Award for his humanity and compassion.

"Black Hawk's Mission of Peace became my obsession," said Phillip Gottfredson, "I asked myself over and over why a man who had suffered so much anguish and pain in his final years pleaded for a peaceful end to the war was treated with such disrespect? He didn't surrender, a man like Black Hawk wasn't a quitter. It was more profound than that. Something he believed deep inside. And that became my journey to understand Black Hawk's Mission of Peace. It was a journey that took me 20 years living with First Nation people and understanding their spiritual beliefs."

Why did the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and its leaders make a mockery of the teachings of Jesus, never showing compassion or respect for the dead or the living descendants of Chief Black Hawk? Why have they never expressed any regret or asked for forgiveness? It's logically untenable for "Latter-Day Saints" to judge Indigenous people as "barbarians, savages and heathens."

Brigham and his followers' lust for domination, subjugation, and riches may have won the war, but it cost them dearly. "Many of our ancestors lost their humanity leaving behind a legacy of moral ambiguity contradicting their most fundamental religious beliefs," said Phillip. "For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?" -Mark 8:36

Note: My late friend, Marva Loy Egget of Spring Lake, Utah played a major role in burial arrangements, while the coffin, and headstone were donated by citizens of Spring Lake, many whose ancestors fought against Black Hawk during the war.

The above image of Chief Black Hawk is a sketch by artist Carol Pettit Harding of Pleasant Grove, Ut. It is a forensic reconstruction made from the skull shown in the photo being held by William E. Croff when he robbed Black Hawk's Grave in 1919. With permission from the Timpanogos Nation, Phillip B Gottfredson comissioned Carol to do the sketch for his book My Journey to Understand Black Hawk's Mission of Peace.